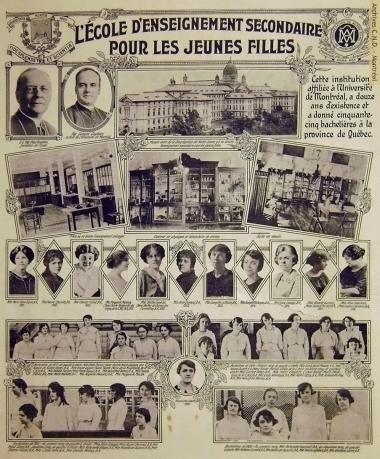

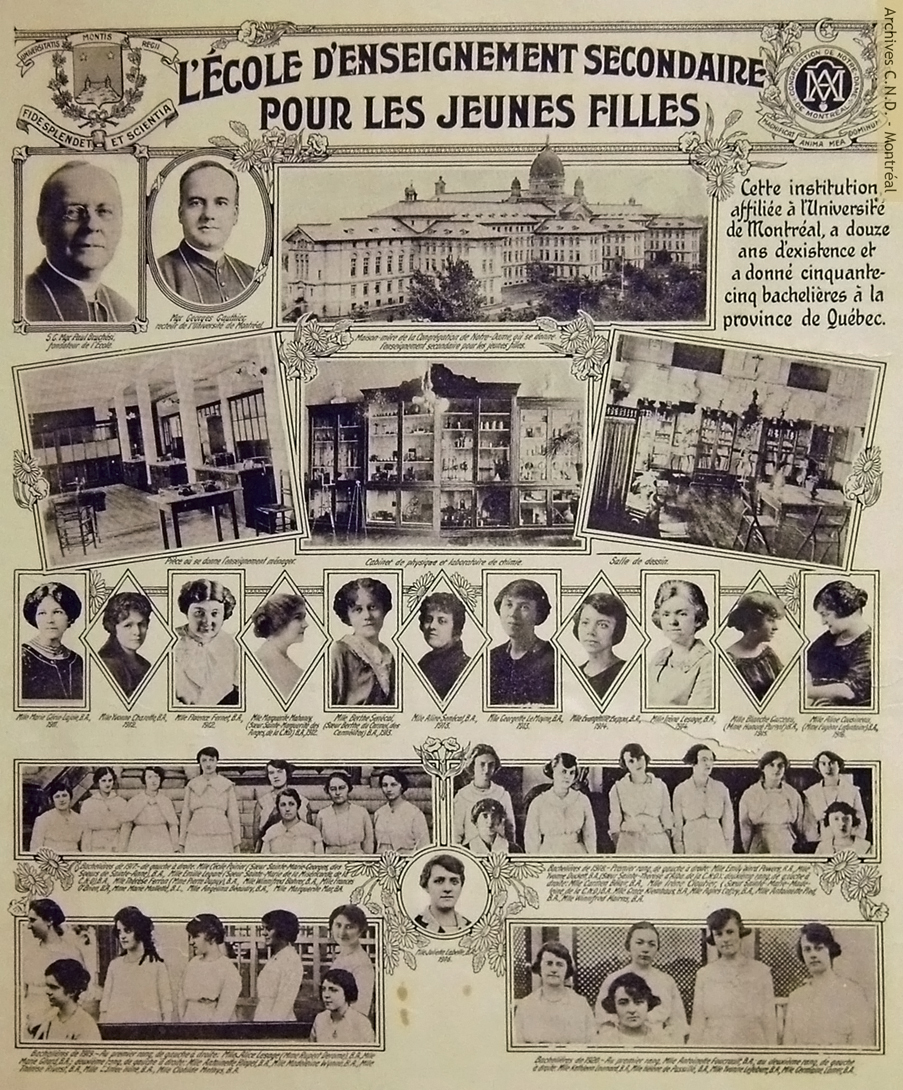

The first half of the 20th Century saw some of the worst disasters the world had yet known: two world wars in which millions died and between them an economic depression that impoverished millions. By the end of the Second World War, weapons of mass destruction had been invented that for decades increased tensions in the Cold War between the West and the Communist Block. Yet some good emerged even from so much anguish. One result of the First World War was that Canada completed its passage from a British colony to a mature and independent partner in the British Commonwealth of Nations. Another was the beginning of the recognition of the right of women to vote in parliamentary elections, though this did not extend to the Province of Quebec until 1940. Many women entered the work force during the wars and opportunities for women in the field of higher education and even in public life continued to increase.

In the period of prosperity that followed the Second World War, Canada saw another increase in population due to an influx of immigrants from Britain and other European countries such as Italy. Like other countries in the West, Canada’s population grew through the birth of a large number of children born to families already established here, part of the group that became known as the “baby-boomers”.

This period of hope, optimism and rising expectations culminated in the Western World with the beginnings of unrest on university campuses, in Quebec, with the beginnings of the Quiet Revolution and in the Roman Catholic Church throughout the world, with the convocation of the Second Vatican Council by Pope John XXIII.