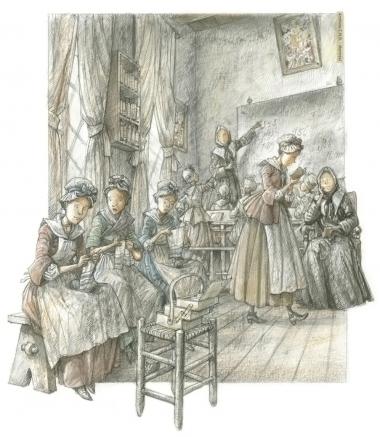

The months immediately after the signing of the Treaty of Paris brought the departure of the French colonial officials and military and some of the leading families, the installation of a British military government and an influx of merchants, land speculators and settlers from the American colonies and from Britain.

However, it was not yet clear that the final destiny of the territory that would become Canada had yet been permanently decided. France was building up its navy and might perhaps reverse its defeat. Relations between the American colonies and Britain were increasingly fractious.

The desire to obtain the loyalty of their new subjects in the colony that became the province of Quebec led the British to pass the Quebec Act in 1774. This act guaranteed freedom of religion to the colonists and restored the old French civil law that had been suspended after the Conquest. It extended the borders of the Province of Quebec to include all territories that had been under the governor of Quebec during the French regime.

The American Revolution once more brought war to what had been New France: an American force occupied Montreal in 1775-1776 but was unable to take Quebec. An important consequence of the Revolution for Canada was the large influx of Loyalists, those American colonists who had remained faithful to the Crown and had to flee to avoid persecution. While some of these settled in the French villages most of the more than 30,000 of them settled in the Maritimes, in the Eastern Townships and in what is now Ontario, opening up territory that had been wilderness.

On the economic scene, 1783 saw the founding of the North West Company with headquarters in Montreal. This company which entered into victorious competition with both the Hudson’s Bay Company in the north and American trade to the south, helped make Montreal the economic hub of the new country that was emerging.