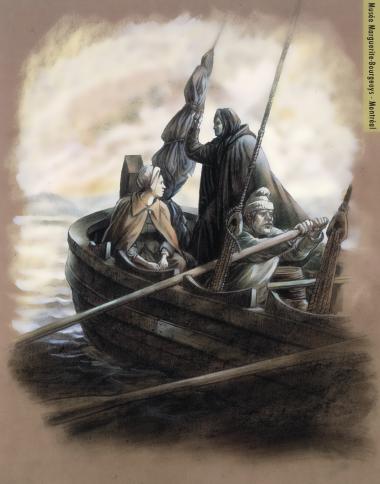

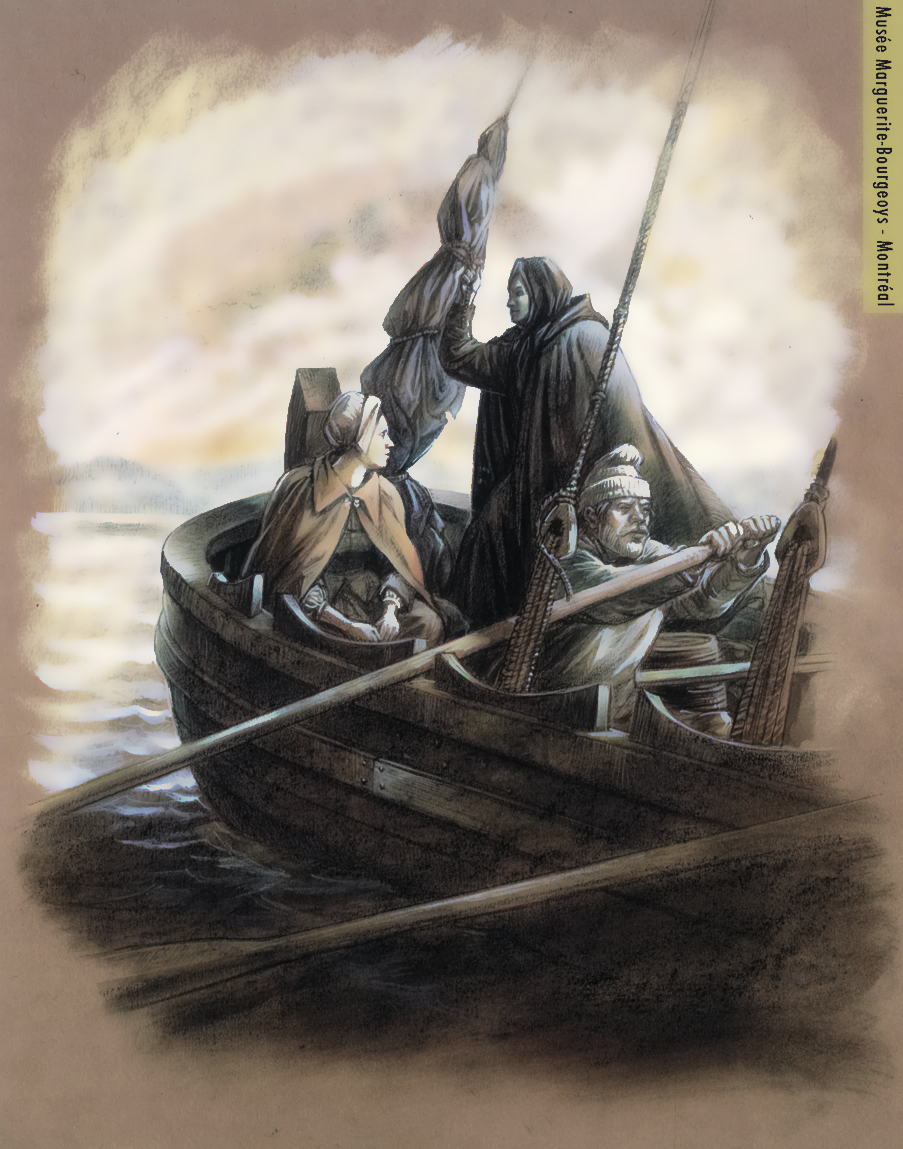

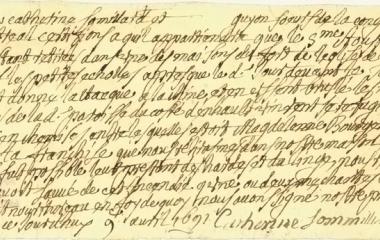

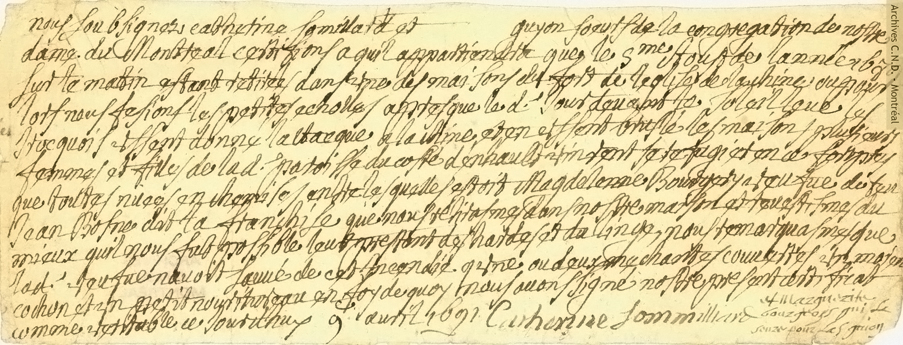

When Marguerite Bourgeoys arrived in Québec in September 1653, she was part of a group known as the “Great Recruitment”, the “colonists who saved Montreal.” Many of the founders of 1642 had left or died. The entire French population of New France had been estimated at about 700 persons. Along the Saint Lawrence, these were to be found at Québec, established in 1608, Trois-Rivières, established in 1634, and Ville-Marie (Montreal). While certain native tribes, the Algonquins and the Abenaquies, had become allies of the French, the French were most often at war with others, especially the tribes of the powerful Iroquois Confederacy. Marguerite Bourgeoys reached Ville-Marie in mid-November after staying in Quebec to care for the men who had become ill during the ocean crossing. The colonists of 1653 with whom Marguerite arrived more than doubled the population of Montreal whose continued existence had been called into serious doubt by its exposed position and its dwindling population. Like most of the Montreal population at this dangerous time, she took up residence in the fort.

1653-1699 - “The Colonists who Saved Montreal”

A Precarious World

For the Sake of Families

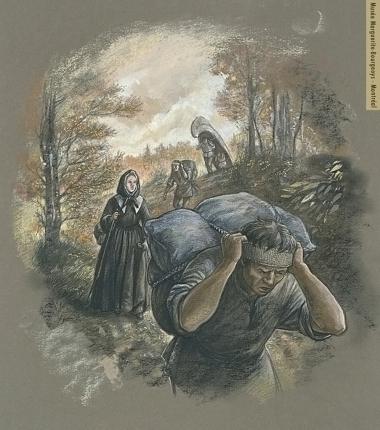

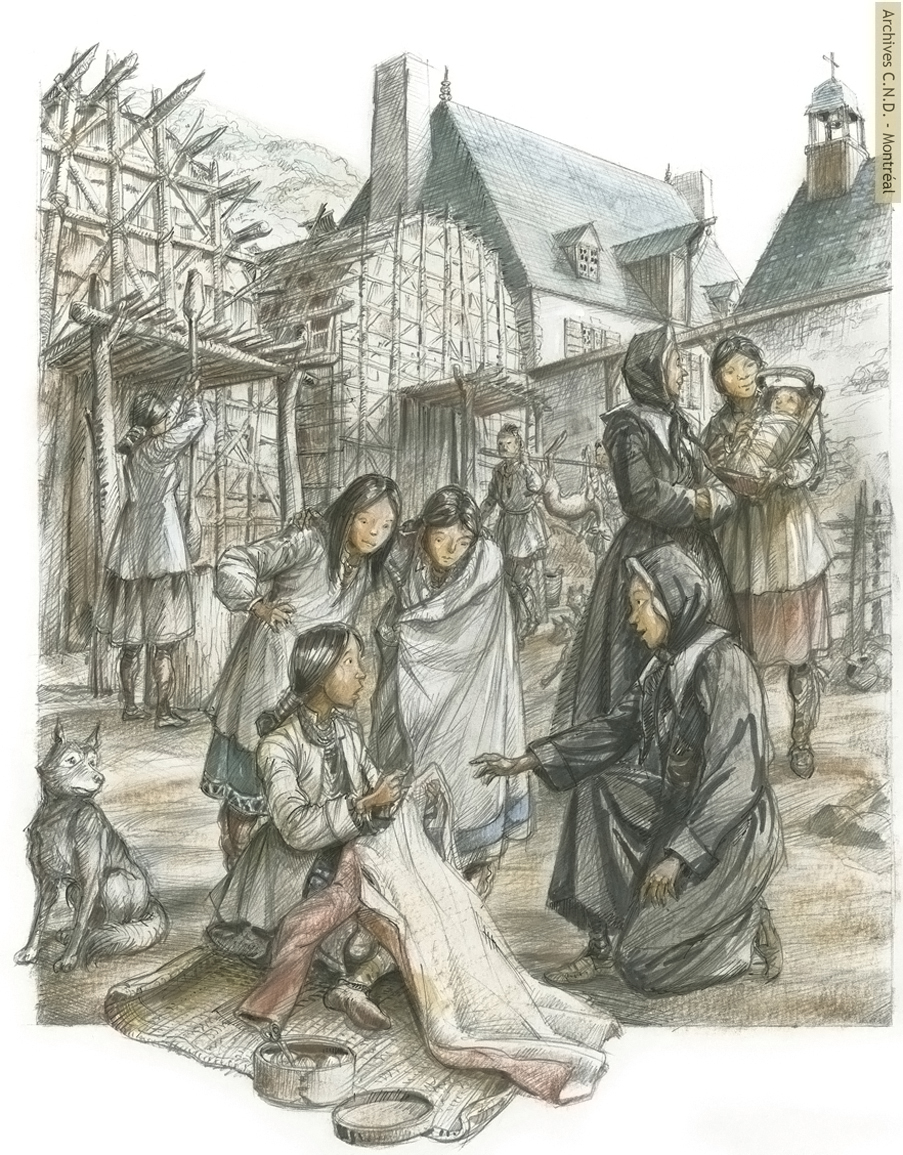

Marguerite Bourgeoys early recognized that the work of education has its origins in the home. Even on her very first voyage to Canada she was entrusted with the care of a young girl on her way to Montreal in the hope of marrying and establishing a family there. Because there were too few children on Marguerite’s arrival to warrant the opening of a school she went from house to house in the tiny settlement meeting the women already there and teaching them to read and write. The support and education of women was an essential and important part of the work undertaken by Marguerite and the companions who would join her to form the Congrégation de Notre-Dame de Montréal. This is especially true of the help given to the young women, known as “les filles du Roy”, recruited between 1663 and 1673 by the royal government to emigrate to New France, to marry and to establish families. Marguerite met them at the shore, befriended them and took them to live with her until they found suitable husbands. She and the members of her Congregation taught these hopeful and courageous women, most of them from urban backgrounds in France, the skills they would need to survive and even prosper in their new environment. Wherever the Congregation went to educate children, the sisters always arranged for the women of the settlements to come together on Sunday for informal religious instruction and for mutual support and encouragement.

A Congregation Without Borders

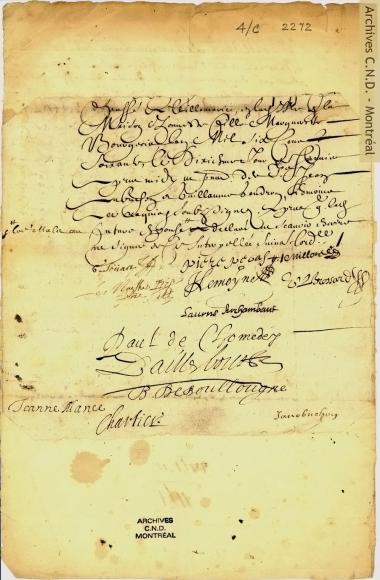

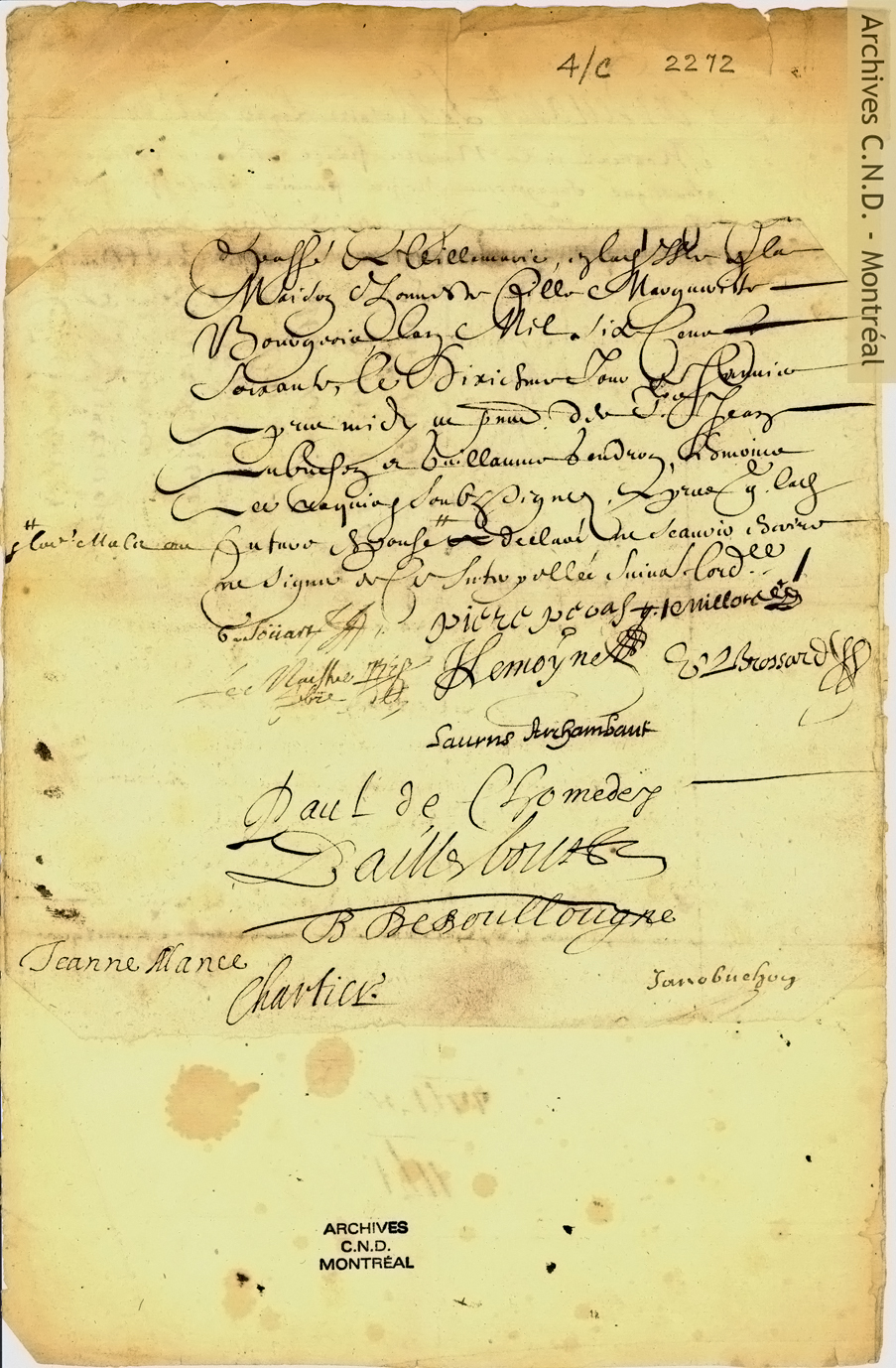

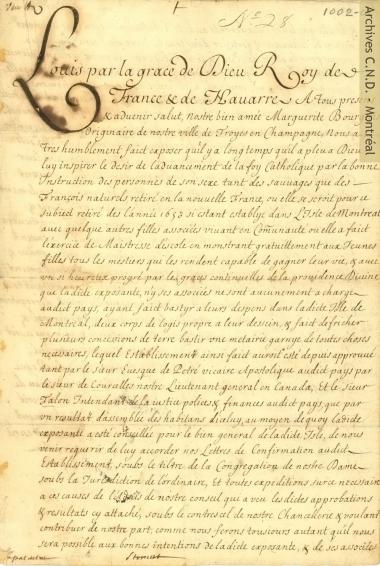

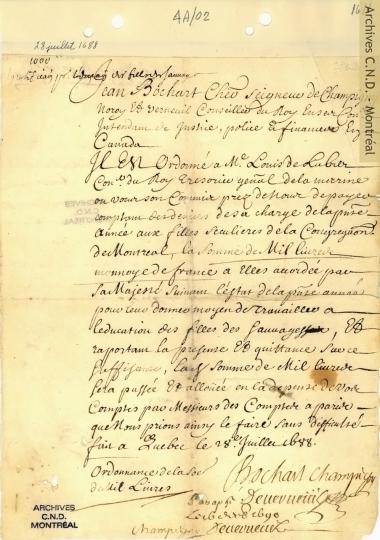

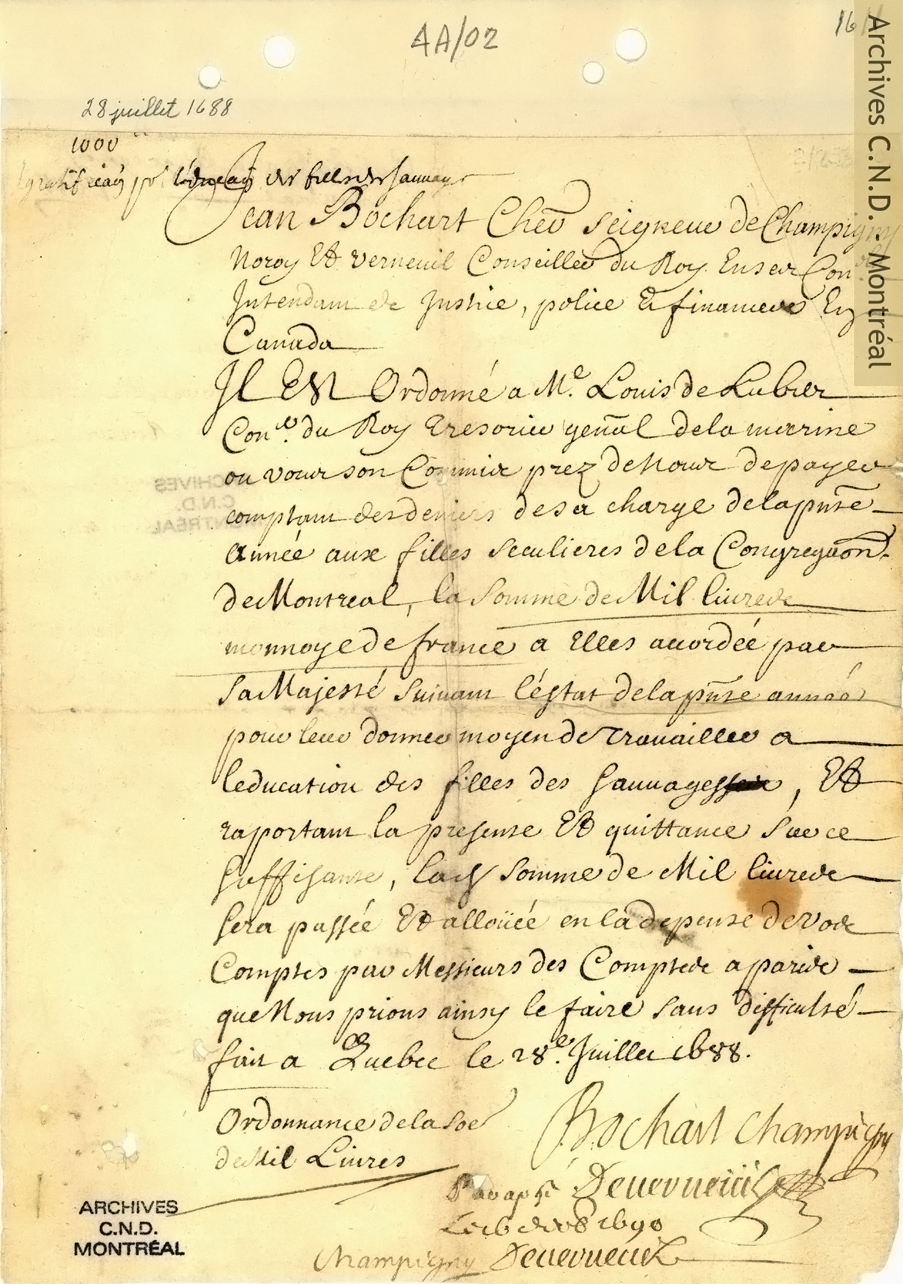

When she left alone for Canada in 1653 it seemed that Marguerite Bourgeoys was leaving behind her dream of a religious community of women who would follow in the footsteps of Mary, the mother of Jesus and the other women disciples in the early Christian Church. But her spiritual director assured her that what God had not willed in Troyes, God might bring to pass in Montreal. And so it proved. In 1658-1659 Marguerite made the difficult journey back to to her native land. She returned with four companions pledged to live with her in community and to teach the children of the settlers and of the Native Peoples. The usefulness of the work of this little group of women, uncloistered and so able to go out “wherever charity or need required” and to offer hospitality to those in need., was soon recognized by both the civil and religious authorities. In 1667, during a visit to Montreal of the governor and the intendant, an assembly of the colonists voted unanimously to support the application of the Congregation for letters patent. In 1669, Bishop Laval authorized the members of the Congregation to teach throughout his diocese, a territory that included all of New France. In 1670, Marguerite went again to France and returned in 1672 not just with new recruits for her Congregation but also with the letters patent signed by Louis XIV. By the end of the 1670s, the first North American women had begun to enter the Congregation, of both Amerindian and French descent. The war that engulfed the colony in the final decade of the century brought into the Congregation women of English descent who had been brought to Montreal as captives but elected to stay. Bishop Laval gave his first canonical approbation to the Congregation in 1676. In 1698, after a struggle to maintain the uncloistered character of the Congregation, its rule of life received canonical approval and its members made public profession of vows for the first time.

Ready to go anywhere they are sent

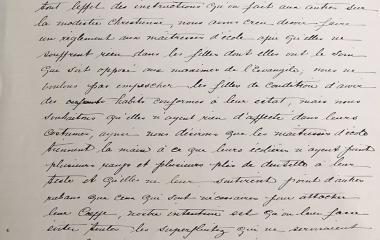

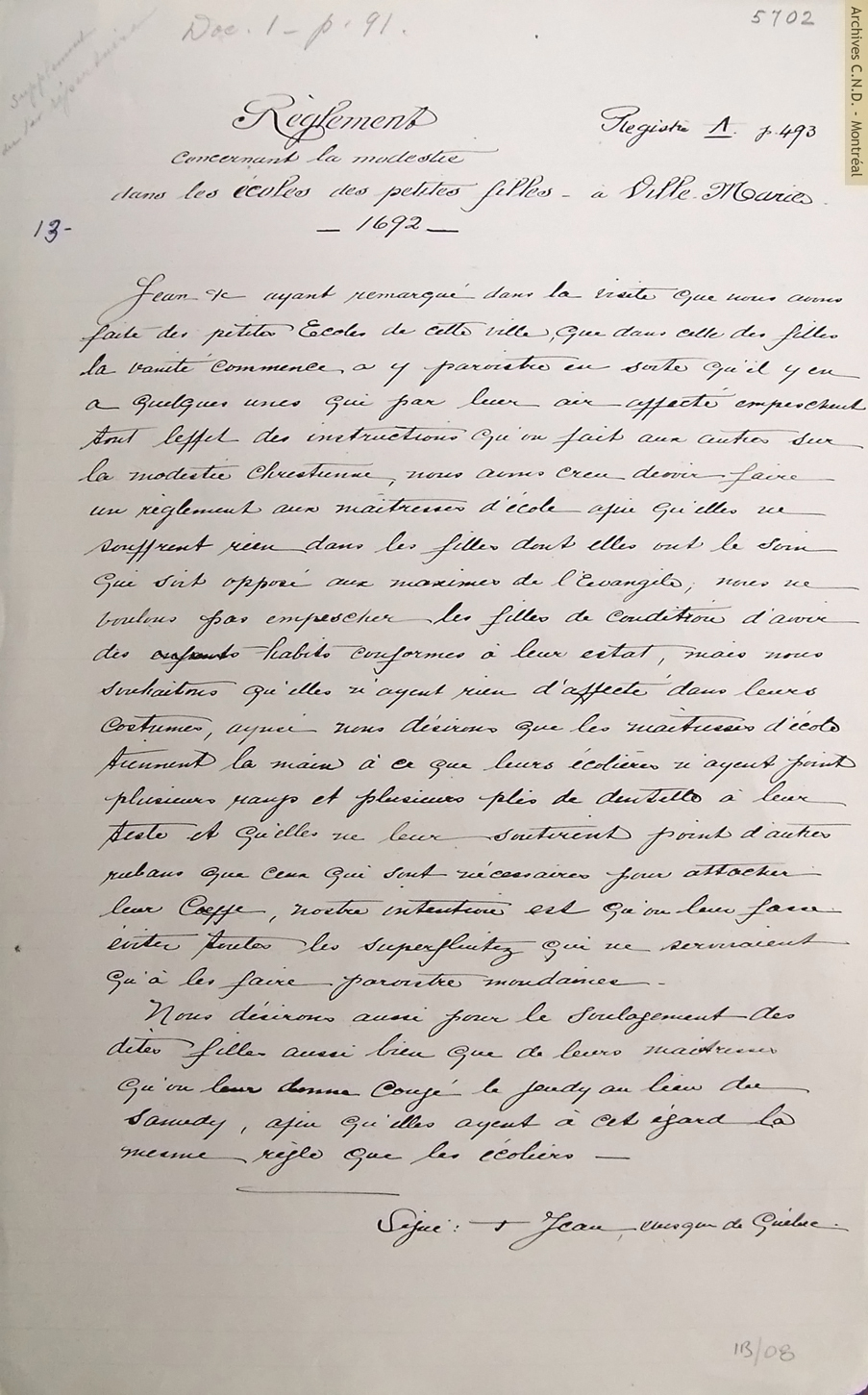

On 30 April 1658 Marguerite Bourgeoys opened Montreal’s first school, the first public (free) school for girls and boys in Canada. The school was a converted disused stone stable and the children themselves had helped prepare it for their occupation. Because they were uncloistered and because they were authorized by the bishop, Marguerite and her companions soon extended their efforts far beyond Montreal. Almost as soon as she was joined by the women who formed the nucleus of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame, the group began to undertake what were called “travelling missions”: they went out, singly or in pairs, to the smaller settlements along the Saint Lawrence River to spend several weeks teaching the young people in preparation for First Communion, a rite that took place on the threshold of adult life. As the century progressed and the Congregation increased in numbers it also established permanent schools at Champlain, Pointe-aux-Trembles de Montréal, Lachine, Île d’Orléans, Québec, and Château-Richer. One of their number may even have reached Port Royal in what is now Nova Scotia. They also worked among the Native Peoples, at the Mountain Mission in Montreal and at Sault Saint-Louis. Besides teaching the children and receiving and initiating the “filles du roi” in the demands of their new life, the sisters of the Congregation also opened a trade school intended to teach poor women how to earn a living. Under the direction of Marguerite Bourgeoys, through the skill and labour of the sisters, the Congregation was self-supporting and so able to offer its services for free, an important factor in winning the approval of the colonial authorities.

Educating for Life

Marguerite Bourgeoys knew that she was engaged in the building of a new society. Like Pierre Fourier, the great educator with whose ideas she was familiar, Marguerite Bourgeoys saw the work of education as of paramount importance in determining the future of society. The primary educational aim of Marguerite Bourgeoys and of the Congregation was the transmission of Christian faith and values. For Marguerite Bourgeoys these were summed up in the commandment to love God with all one’s heart and mind and soul and to love one’s neighbour as one’s self and, she added, to so act that the neighbour found it easy to return that love. In school, the children learned the basic beliefs, prayers and duties of a Christian. But, again like Fourier, she recognized the importance of imparting to her pupils the knowledge and skills necessary to enable them to earn a living and to play their role in society. She required that the sisters in her Congregation become “knowledgeable and skillful in all kind of work.” Besides catechism, they taught reading, writing and counting and also the skills needed to run a pioneer household and to bring up children. These were many in a world where most manufactured goods had to be imported from France at great expense so that settlers had to provide for themselves as much as possible. The women needed to know about cooking and preserving, about sewing, mending, dress-making and other handicrafts, about the care of animals, as well as planning for the future and keeping accounts. Commentators suggest that the sisters of the Congregation also imparted such intangibles as grace and good manners.